CHAPTER V. THE CANALS: Macfarlane’s Narrative Concluded

Editors Note: From now on, in our original reception of them, the Martian Messages were more disjointed than in the earlier stages of MacFarlane’s continuous chronicle. Although they have been edited and remolded since by their original sender, I leave them here with some flavor, at least, of their fragmentary nature, so that readers will understand something of our own mystification as we listened to them at Larkwell.

. . . IT WAS, I firmly believe, the reappearance of Malu which brought back to health my old friend Dr. McGillivray. As you know, he never fully recovered—there were long lapses into lethargy and forgetfulness; and certainly his blindness never left him; but at least he retrieved some of his old verve—has been, among other things, sufficiently his old self to help me in the construction of this method of radio communication to you on Earth.

Nothing I can say can describe our joy at Malu’s appearance. It was a strange reunion—his silent thoughts of welcome contrasting with our own noisy exclamations, as our feelings were expressed in our own less delicate way.

As we “talked” together beside the gleaming Albatross on the plain, we learned what had happened in the course of the last great battle before our previous departure—the battle which formed the climax to our book The Angry Planet, my dear John. Indeed, we more than “learned”; for side by side with the words translating themselves inside our heads as Malu’s thoughts flowed into us, there came a full communicated vision of all that had befallen that day.

It seemed that the blast of the Albatross’ take-off had momentarily stunned the attacking Terrible Ones. Malu himself was thrown clear of the group surrounding him; and with his greater rapidity of movement was able, on recovery, to escape around the rim of the great seething saucer of lava in which lay the dying city of his tribe.

By now, the force of the volcano had almost spent itself. The Terrible Ones were in confusion and rout, their great clumsy egg shapes slithering back toward the hills. By the time Malu had organized his scattered troops into a striking force, the last remnants of the invaders had dispersed; and so the battle ended, barely an hour after we ourselves had left the fearful scene of it.

The terrible ones were in confusion and rout.

“And oh, my friends,” said Malu, “the desolation in our poor dwelling place when all was done! Only a few of our homes of glass remained unruined, the floor of our valley lay littered with the dead from the battle itself and from the lava poured down upon us from the angry mountain. Sadly, we who were left set to gathering together as many of our friends as we could find. Among them, let there be praise!—lying helplessly under the dead form of the Chief of the Terrible Ones—was our Leader, the great intelligence controlling us, known to you as the Center. He was sorely wounded, but alive, and able to direct us in our work of rescue.

“We left our shattered city—it was beyond all mending. We pushed southward, toward other centers of our race among the hills. In one of them we found refuge for a space, but then moved on again, until at last, in another small hill valley, we came upon some uninhabited glass bubbles, and there took to dwelling. . . .”

Thus they built again their peaceful and benevolent way of life; until one day there came—no more than faintly at first, as the telepathic impulses weakened over the distances involved—an impression that a strange shining object had fallen from the skies and rested far to the south. Eventually, Malu himself came to an understanding that his legendary friends from the remote world of “Earth” had returned; and so set off, guided by the plants on the plains . . . and found us at last, and succored us. . . .

I hasten—I must hasten; there may be little time to complete my story. Already I am desperately aware of . . . of—an attempt to control, to control . . .

(This single brief disjointed message here broke off; and for two anxious nights there was no further communication from MacFarlane—despite the arrangement he had made to broadcast at regular periods. Toward dawn on the third night the Morse began again—somewhat hastily in its transmission now, as if the sender were in some fear; yet he made no references to the source of such disturbance for some further nights. And then—however, to proceed in order:)

—The Canal. The Canal has crept closer and grown all around us. And the Vivore, the Vivore . . .

(This message too broken off—with a disjointed repetition over and over again of the single word, “Vivore.” On this night reception was extremely faint and difficult—we were not even sure of the word . . . and this, as will be seen, was a contributing factor toward christening the terrible new Martian creatures encountered by the explorers “Vivores.”)

—the Center. His agitated explanation . . . and so a first glimmering of the nature of the Cloud. But this came later—I can resume now the account of our progress from the time of Malu’s discovery of us on the plain: there is less attempt tonight at control. . . .

We traveled with him to the new community established in a range of mountains far to the north of our landing place. Because of the lesser gravitational pull I was able to carry sufficient food to last the Doctor and myself for many months and, as will be known, this store could be augmented from the edible leaves of the foothill trees.

So once more we entered into the life of the Beautiful People; re-encountered the tall, Malu-like shape of the Center himself—were welcomed solemnly as he sat (crouched, rather) on his great central humus pile in the largest of the bubble houses.

I had brought a small tent with me from the Albatross—the identical tent in which we all had lived on our last visit. And so we dwelled through the long months of Mac’s gradual recovery, contentedly enough in our communication with our old friends—bathed once more in that strange sense of quiet benevolence we all had experienced and commented on before as being a quality of life among the Beautiful People. In the long balmy summer season we restored our faith; once more, as time passed and Mac came back to normal, the unaccustomed fragrance of his pipe went drifting in the rare Martian atmosphere and, lying back by his side, I watched the two little moons go circling above our heads . . . and described to him as well as I might the alien but familiar scene surrounding us as the quiet slender shapes of the Martians went gently about their business.

Yet I hardly needed to interpret to him in this way after a time. Except for the occasional lapses into lethargy, it was as if, in his blindness, he had developed the art of telepathic contact with Malu and the Center to an extent which I, imperfectly equipped because I had all my usual senses, could never achieve. The immense mass of knowledge gained in this way by McGillivray will become available in due course to humanity, when once we return to the Earth—if indeed, from our present impasse, that will ever be possible! I pray to heaven that it will; for now that we confront the Vivore—now that it surrounds us, makes veritably to swamp us . . . the children, perhaps the children—

(Message broken. This irrelevant reference to the children—MacFarlane always thought of Paul, Jacky and Mike as “children”—kept recurring from now to the end. What it meant we did not know—the reference invariably followed a spell of fragmentary reception, broken messages. And sometimes there were periods in MacFarlane s account which made no sense at all—were frankly a kind of gibberish. Thus on one occasion, after some further nights of silence, a message came which, literally transcribed, ran as follows:)

“—No—not . . . pera—requuullian . . . jeje jeje . . . but the children—if children children—cont att at cont . . . will try but try but trrry buuttt—chil—chiiilll . . . save save save . . .”

(One more night of comparatively uninterrupted reception followed—a long session lasting almost four hours, all at high speed. It will be noted how abrupt MacFarlane’s narrative style had become; as if, as the Vivore approached—whatever the Vivore might be—a sense of growing panic swamped all other considerations, forcing him to be straightforward, even brusque in his manner of delivery.

The narrative continues, therefore:)

And so once more, as on the last visit, the Albatross was dragged across the plain by the willing Martians, to rest as closely as possible to the Center’s headquarters without being in any danger from possible further volcanic eruptions. She was little worse after her months of isolation in the long mild summer, but with winter now nearer, and bitter as we knew, she had to be brought to shelter in a small range of foothills. She was needed moreover for living accommodation for Mac and me, who could not stand the overheated dampness of the bubble houses.

Mac was now almost himself again. His long “conversations” with the Center; and at last the hint of danger, over.

Mac had spoken with the Center on one occasion for a long long time; and when he and I, later, were settled together for the night in the cabin of the Albatross, his expression grew serious. For my part, less skillful in communication with the Center than he was, I had not fully understood the significance of the session. I knew only that at last Mac had been trying to find out the nature of the Yellow Cloud where it came from and what it was.

“And there came from him,” said Mac slowly, referring to the Center, “—there came from him, Steve, such a wave of fear as I have never known these creatures to express before!”

“What was it?” I asked. “What was the Cloud, Mac?”

“I don’t know—even yet I don’t know. The Center did not know—not fully. It was as if—and you must realize that I am only groping here, Steve, for the Martians plainly cannot communicate anything of which they themselves have had no experience—it was as if the Cloud were some kind of legend among them. It’s something deeply feared that lingers on only as a race memory—and even then only in such highly intelligent creatures as the Center himself. You find the same thing on Earth, among certain primitive tribes—a lingering something that their ancestors knew and feared and passed on to them in the form of myths through the years.”

“But what kind of myth, Mac? There must have been something—some kind of image from the Center?”

“There was! A very strange one. I hardly dare to think of it, Steve, for it connects with a dreadful kind of . . . vision I had when I was snatched into the Cloud—something that comes back to me now only imperfectly, although I have the impression that I understood it better then, when my mind was gone, than I do now. . . . There were two images from the Center—rather three. The first was a picture, transmitted from his mind to mine, of the Yellow Cloud itself, as we saw it—sweeping at immense speed across the plains. The second image was vaguer—less understandable—and the only words that came into my mind to express it were, ‘The lines—the creeping lines . . .’ ”

“The lines?”

“The only words, Steve, except that in my mind they had a double translation. You remember I told you during the flight about the Italian astronomer, Schiaparelli—his discoveries in the 1870’s—”

“The Canals,” I said. “It was Schiaparelli who discovered the Canals—”

“Quite so—but he used the word canali to mean only lines or markings—veritable channels on the Martian surface which he thought he saw. That was the other word which came into my head during my session with the Center: canali, Steve—the creeping canali.”

“But Mac, it doesn’t make sense!”

“It might—it might make devilish sense before we’re done! Steve, tell me—you can see, old friend, and I cannot—as you look out across the plain sometimes—”

He broke off—a look of bewilderment came across his face. I recognized the symptoms too well. The old lethargy was returning, the lingering effect of his immersion in the deadly Cloud—perhaps in the association between his conversation with the Center and his terrible experience. Desperately I tried to bring his thoughts back to the moment.

“Mac—Mac! The third image—you said there was a third image from the Center—”

But all that came from him was the one word from his old nightmare: Discophora . . . and a sudden impression in my own mind once more of something monstrous—white—jellylike . . .

I looked out through a porthole in the dying evening light. Did I imagine it? Or was there, far out on the plain, verily on the horizon, a new strange tinge of darker green—a kind of ridge . . . ?

So little time, so little time! When morning came I saw indeed that there was, on the far plain, a belt or band of some dark green substance—and that it was larger a little than I had supposed the night before.

Mac’s illness worse—no sign of recovery from the new bout that had assailed him. Two days . . . and in those two days, before he did recover, and I could tell him, the darkness on the horizon had intensified—was something that moved—and moved nearer and nearer toward us. . . .

Among the Beautiful People a rising sense of uneasiness—a continuing quivering fear from the cactus plants nearby.

Mac’s recovery at last; and an intensification of our experiments to contact you on Earth. The exposed seam of mineral deposit in the foothills: our hastily rigged transmitter here in the cabin of the Albatross, the leads going down to the seam . . . night after night—my messages into space, as always and always the menace approached across the plains. At last the first imperfect return messages—the fabulous coincidence of the airstrip . . . and so I have told you our story as always It has drawn nearer . . .

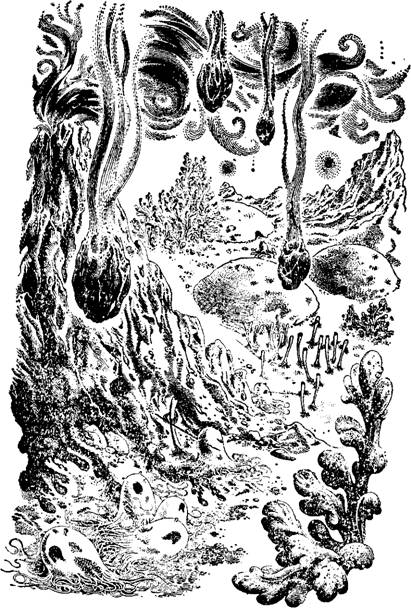

We have not dared to move from the ship. Malu now with us—but Malu is able to move outside on occasions, through the double air-lock door, for the yellow spores have no effect upon him other than in an attempt to control him mentally. The others gone—the city in the hills abandoned. Only Malu and ourselves . . . only—The Creeping Canal! The dark green, viscid line approaching across the plain, nearer and nearer! They control—they control it: the Vivores . . . !

The Canal—the long serpentine line of it, the waving traveling swamp . . . closer and closer and finally surrounding us. And at last, the first of Them . . . the swamp now all around, all around, and we dare not move from the cabin. As it has been this past ten days while I have struggled to continue contact with you. I dare not relax, dare not. They control—they can control . . . !

I saw the first—some days ago I saw the first. There, in the swamp surrounding, in the hot steam of it . . . white, monstrous. Discophora! The great white monstrous jelly—and waiting, waiting for us, waiting for us, waiting . . .

I will not—will not!—the children, the children . . . !

(Message broken, and nothing for four nights; then some further disjointed gibberish, quite unintelligible; and at last, suddenly clear, one final desperate cry across the silent void of space, the broken, helpless message as I have already described it in my own first chapter:)

. . . Save us—in heaven’s name try to save us! There is one way—one way only. We are lost—you must save us. Somehow—come somehow. Bring the children—the three children. It is the only way to save us. I cannot, cannot, cannot explain. Only bring the children, somehow. That will save us, that alone. It does not matter how long. We are safe, safe, for many months, years perhaps. But we will perish at the last if you do not bring them. Do not ask why. Find some way—some way. Kalkenbrenner—try perhaps Kalkenbrenner. Bring Paul and Jacqueline and Michael. Ask no questions—no time, no time to answer; but bring those three to Mars or we are lost . . . !

Then silence. From that moment onward, silence absolute. Never again did our small receiver by the airstrip chatter its thin rare messages from across the void.

In the chill of the early dawn we regarded each other, white-faced—Mackellar and Archie, Katey and myself, the two young people who had joined us and attended the few final sessions when the broken messages were coming through.

We regarded each other, the silence filled by the low sullen roar of the Atlantic beyond the moonlit airstrip. Our thoughts were full of indefinable nightmare—a sense of intolerable danger to our friends so many millions of miles away. And of resolution. We did not understand—how could we?—what could it mean that only the presence of the three young people could save MacFarlane and McGillivray? But we knew that the desperate message would never have come unless indeed, in some alien manner connected with the unutterable strangeness of life on the Angry Planet, it was the only way.

We trusted MacFarlane; and therefore we had to act—somehow we had to act—so that the travelers might be saved from whatever monstrous creatures menaced them—of whose nature we had no true conception.

And MacFarlane had given us the hint himself as to how the impossible journey might be achieved a third time in human history.

Dr. Kalkenbrenner.